Treatment

Due to a dysfunctional epidermal barrier, xerosis is common in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD). By minimizing transepidermal water loss and improving stratum corneum hydration, topical moisturizers can help reduce the signs, symptoms (such as itch), and inflammation in AD.1 Moisturizers are the primary therapy for AD as they have been shown to minimize erythema, fissuring, and pruritus.2 While applying moisturizers soon after bathing can be employed to improve skin hydration, updated recommendations for AD refractory to moisturizers includes the use of additional medicated topical therapy.1,2

Additional topical therapies

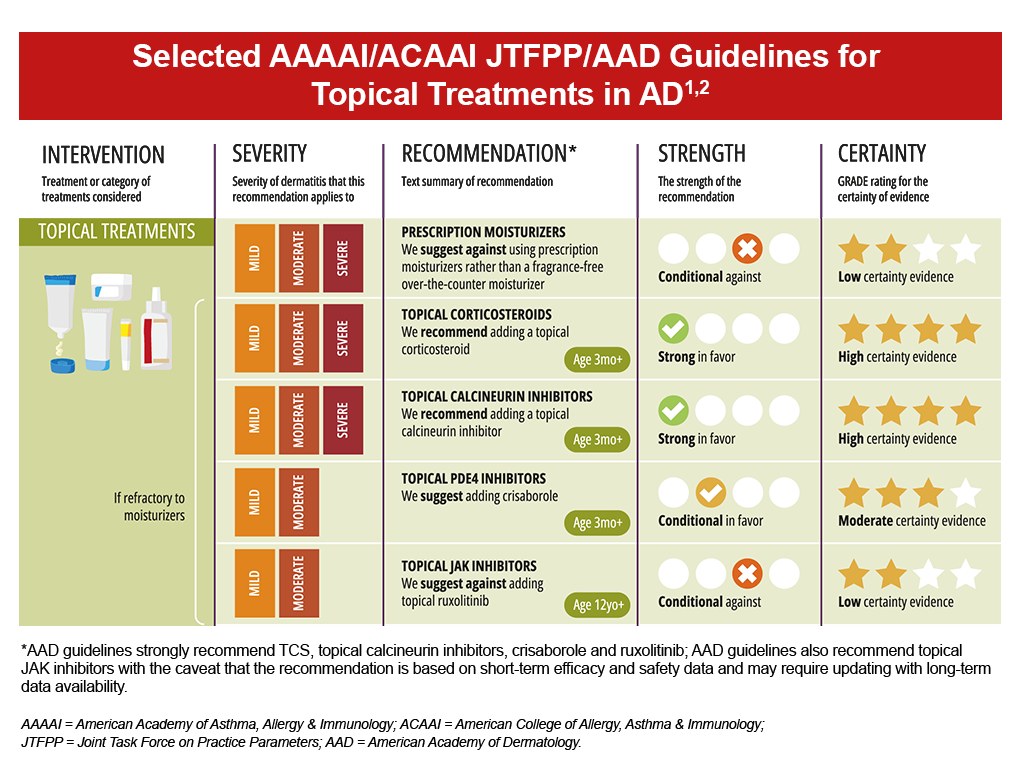

Topical medications may be used in combination as they have different mechanisms of action and can simultaneously target different aspects AD pathogenesis.1 Topical agents are also often used in conjunction with systemic or phototherapy in patients with moderate-to-severe AD.1 Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of various therapies, including topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors for uncontrolled AD, and topical PDE4 inhibitors for mild-to-moderate AD; however, guidelines differ on the use of topical JAK inhibitors.1,2 Occlusive dressings (wet wrap therapy) can also be utilized to provide a physical barrier to scratching while also allowing for greater topical agent penetration and hydration.1,2 Low or mid potency TCS are typically used with a moistened cotton suit, gauze or layered bandages.1

- Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are the mainstay of anti-inflammatory therapy in AD and are commonly used as first-line treatment across all AD severities and skin regions.1,2 TCS suppress immune responses and inhibit the release of proinflammatory cytokines, and are recommended in uncontrolled AD refractory to moisturizers as well as for continued intermittent flare prevention after remission.1,2 Available in several potencies, consideration of anatomical site and course duration are key elements to therapy selection.1 High potency TCS and prolonged courses of lower potency TCS can be associated with risk for atrophy, telangiectasia and striae.1,2

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) are a class of anti-inflammatory drugs that inhibit calcineurin-dependent T-cell activation, thereby blocking the production of proinflammatory cytokines and mediators responsible for the AD inflammatory reaction.3 Available TCIs include tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, and are recommended with uncontrolled AD refractory to moisturizers as well as continued intermittent flare prevention; TCIs may also help reduce flares as well as TCS use.1,2 Combination therapy with TCS has been shown to achieve better outcomes than monotherapy with TCS or TCI.1 Of note, tacrolimus has been observed to have greater clinical efficacy, however, is only available as an ointment whereas pimecrolimus is available as a cream.1 Alternatively, pimecrolimus may be a consideration for those who prefer creams, have milder disease or with local reaction sensitivity.1 The most common side effects with TCI use are local stinging and burning upon application.2 Once per day application is suggested to help simplify the treatment routine and minimize side effects.2

- Topical PDE4 inhibitor crisaborole is a non-steroidal ointment that targets phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), which can lead to increased production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. 4 Based on studies, this topical therapy may be more beneficial with mild to moderate AD that is refractory to moisturizer therapy and for those who prefer non-steroidal treatment options.2 Side effects of stinging, burning and pain are associated with crisaborole, and may be more prominent when applying to sensitive areas.1,2

- JAK-STAT inhibitors target the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) intracellular signaling pathway which is thought to cause inflammation.5,6 Although there are many topical JAK inhibitors in development, only ruxolitinib is available in the United States (US).2 Current guidelines vary on the recommendation for topical JAK inhibitors in AD, largely due to safety concerns related to uncertain associations of increased risk for cancer, thromboembolism, serious infection, and mortality.1,2 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a boxed warning on all JAK inhibitors due to increases in cardiovascular adverse events, cancer, and venous thromboembolism with tofacitinib (rheumatoid arthritis study).2 Due to concerns with systemic absorption, topical JAK inhibitor therapy should be limited to less than 20% of body surface area (BSA) and used in a discontinuous manner to decrease potential harm.2

- Aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists are topical nonsteroidal creams that work by binding to and activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. These receptors downregulate both inflammatory pathways and oxidative stress, and increase expression of proteins involved in the skin barrier.7 Tapinarof was approved by the FDA in December 2024 and does not appear in the most current update of the AAAA/ACAAI JTPP/AAD guidelines.8 Tapinarof is indicated for use in adults and in pediatric patients at least 2 years old. Adverse reactions reported in pediatric subjects were generally consistent with those in adults during clinical trials.9 Most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity with the most common adverse events being folliculitis, headache, and nasopharyngitis.10

- Bleach baths can be controversial, however, may be helpful in infection prevention and bacterial colonization.1,2 Dilute baths are conditionally recommended and have associated mild side effects of dry skin and irritation.1,2 Written instructions are needed to ensure correct bleach type and concentration are used.2

- Antimicrobial therapy may also be necessary to treat infection, however, guidelines recommend against the use of topical antimicrobials in the setting of uninfected AD.1,2

Systemic Treatments

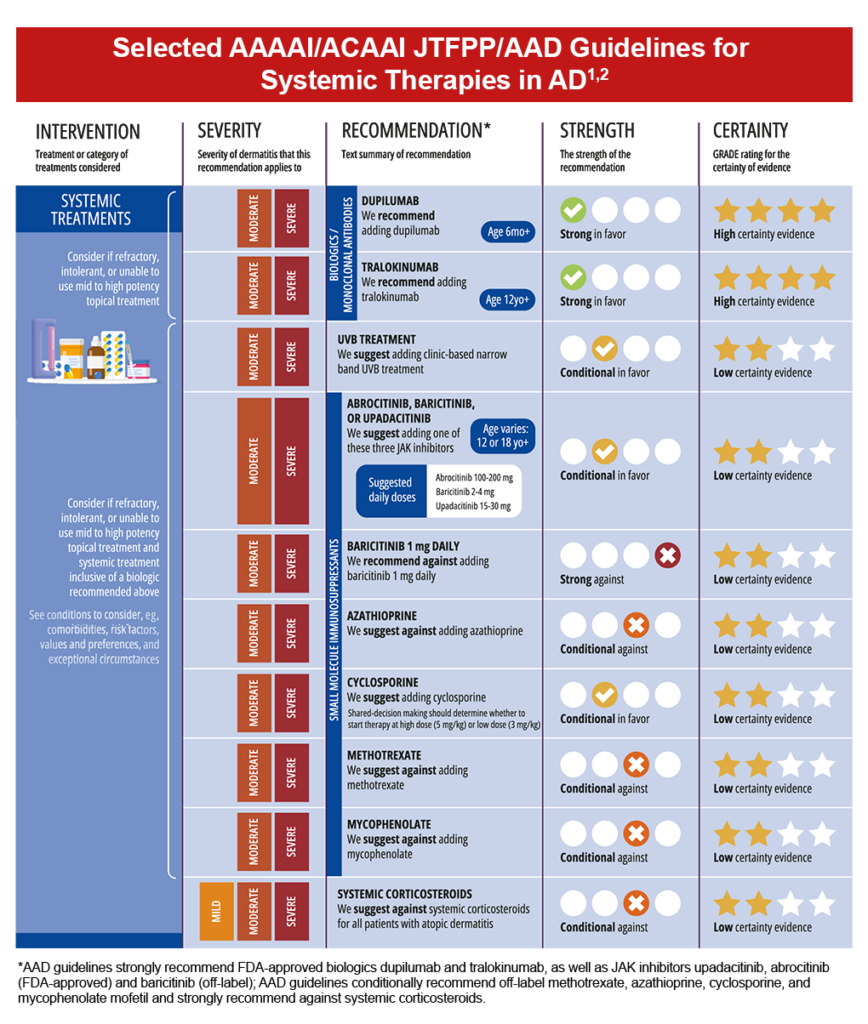

Although topical treatment options are effective in minimizing the symptoms of AD, they may be associated with application site reactions and safety concerns with use over extended periods. Emollients and topical anti-inflammatory agents are often insufficient for individuals with moderate-to-severe disease, leading to the need for systemic treatment options.3,7

Ultraviolet B (UVB) Phototherapy

Phototherapy has been found effective for AD refractory to topical treatment, but has a low certainty of evidence and has a conditional recommendation for use.2,8 Side effects can include sunburn-like reactions and risk of skin cancer associated with UV exposure.8 Accessibility due to frequency of sessions (2-3 times/week over 10-14 weeks) and factors such as travel distance and insurance coverage can also limit use.8

Biologics

Biologics should be considered for moderate-to-severe AD that is refractory or for those who are intolerant to topical treatment.2,8 The addition of biologics to treatment regimens has been shown to improve signs and symptoms of AD, such as itch and sleep disturbance.2 Also, no laboratory monitoring is required before initiating or during continued treatment.8

- Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 cytokine pathways through binding of IL-4 receptor α.2,8,9 IL-4 and IL-13 are key Th2 (type 2) cytokines that can drive inflammation in AD.9 As the first FDA-approved targeted systemic treatment for AD, dupilumab was found to be effective in reducing the severity of moderate-to-severe AD in both adult and pediatric patients by targeting Th2 cell-mediated atopic immune responses.8,10-12 Dupilumab is FDA-approved for the treatment of patients aged ≥6 months with moderate-to-severe AD not adequately controlled with topical therapies or when those therapies are not advisable.13 Additionally, dupilumab is approved for use in other atopic conditions, including moderate-to-severe asthma with eosinophilic phenotype and oral corticosteroid-dependent asthma in patients aged 6 years and older, and as add-on maintenance therapy for adults with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis.13 Long-term safety, including in clinical practice has yielded few major emergent safety concerns and has been considered by an international expert panel as first-line for use in special populations, such as older adults with renal disease, liver disease, viral hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or a history of cancer.8

- Tralokinumab is a human monoclonal antibody binding IL-13, preventing interaction with IL-13 receptors and inhibiting the release of proinflammatory cytokines.14 While tralokinumab has been found to significantly improve signs and symptoms of AD, no head-to-head studies comparing tralokinumab to other systemic therapies have been conducted.8 Meta-analysis revealed somewhat less effectiveness of tralokinumab at 16 weeks compared to dupilumab. Tralokinumab is approved for the treatment of AD in patients aged ≥12 years with moderate-to-severe AD not adequately controlled with prescription topical therapies or when such therapies are not advisable.14

- Lebrikizumab-lbkz is a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-13, allowing IL-13 to bind its receptor but inhibiting signaling through preventing receptor complex dimerization.15,16 As of September 2024, lebrikizumab is approved for patients aged ≥ 12 years with moderate-to-severe AD not adequately controlled with prescription topical therapies or when such therapies are not advisable, based on induction studies over 16 weeks compared to placebo.15,16

- Nemolizumab-ilto is a first-in-class monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-31 receptor alpha (RA) signaling and the related responses of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine release.21,22 Nemolizumab was approved by the FDA in December 2024, so it does not appear in the most current update of the AAAA/ACAAI JTPP/AAD guidelines.8 It is approved for use in adults and in pediatric patients aged 12 and older with moderate to severe AD in combination with TCS with or without TCI when disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies.22 Patients demonstrated statistically significant improvements in both skin clearing and eczema area and severity index scores, and clinically meaningful improvement in itch and sleep disturbance, when compared to placebo during clinical trials. Most treatment-emergent adverse events were mild to moderate in severity and non-serious with the most commonly occurring adverse events being headache (5%) and arthralgia, urticaria, and myalgia at 1%.21,22

JAK inhibitors

Systemic JAK inhibitors also work by blocking the JAK-STAT intracellular signaling pathway, important in the immune response to IL-4 and IL-13.8 This class of therapy is not considered as first-line systemic therapy, but is approved for use in moderate-to-severe AD that has failed treatment with other systemic therapies including immunosuppressants, corticosteroids, antimetabolites, and injectable biologics, or when these therapies are not advisable.8

Higher doses of FDA-approved abrocitinib and upadacitinib have demonstrated the highest efficacy at reducing Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores, however, due to safety concerns, regulatory recommendations are to start these medications at their lower doses.8 Additionally, oral JAK inhibitors are contraindicated in pregnancy and breast feeding; assessing for pregnancy should be performed before treatment initiation.2,8

Since JAK inhibitors are immunosuppressants, evaluating for conditions such as cytopenias, active/latent tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, herpes-zoster, and age-appropriate cancer screening are indicated.2,8 Furthermore, obtaining baseline laboratories for blood counts, liver enzymes, and lipid panels, as well as monitoring during treatment is recommended.8

Immunosuppressants and antimetabolites

Although systemic corticosteroids are commonly prescribed for moderate-to-severe AD, due to the significant risk of adverse events—even with short-term use, they are not guideline-recommended in the treatment of AD.8 Instances where short courses of systemic steroids may be of benefit include as a bridge to other long-term therapies or when no other options are available.8

Besides steroids, systemic immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil may be prescribed off-label, however, they are associated with considerable adverse effects that limit treatment duration.7 These four agents each have their own specific end-organ toxicities besides increasing the risk for serious infection, thus, require ongoing laboratory monitoring for adverse effects.8 Of note, due to potential for renal injury and damage with cumulative dosing, cyclosporine is suggested to be limited to ≤12 months (but preferably less).8

A brief summary of important clinical trials with dupilumab, lebrikizumab, tralokinumab and nemolizumab-ilto can be found below:

Trials in adults (ages ≥ 18 years)

Dupilumab

- SOLO 1 and SOLO 210: Two phase 3 trials (n= 671 and 708, respectively) assessing the efficacy and safety of dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every other week in adults with moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled by topical treatment. Significant proportions of patients achieved Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) 0 or 1 scores with dupilumab weekly and every other week compared to placebo at week 16 (SOLO 1: 38% and 37% vs 10%, P<.001; SOLO 2: 36% and 36% vs 8%, P<.001). Reduced pruritus, anxiety and depression as well as improvement in quality of life (QoL) were observed. Common adverse events (AEs) included nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infection, and conjunctivitis.

- LIBERTY AD SOLO-CONTINUE18: Phase 3 trial (n=422) assessing continued efficacy and safety in adults from SOLO 1 and 2 studies for an additional 36 weeks. Consistently maintained responses to treatment were noted with dupilumab weekly or every two-week dosing intervals vs placebo (EASI 75: 71.6% vs 30.4%, P<.001); longer intervals resulted in diminution of response (EASI 75: every 4 weeks = 58.3%, every 8 weeks = 54.9%). No new safety signals were observed.

- LIBERTY AD CHRONOS19: Phase 3 trial (n=740) assessing dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every two weeks + TCS vs placebo + TCS in adults with moderate-to-severe AD with inadequate response to TCS. At Week 16, a significantly greater number of patients in the dupilumab + TCS groups achieved IGA 0 or 1 compared to placebo + TCS (39% for both dupilumab groups vs 12%; P<.0001). EASI-75 was also achieved in a significantly greater number of patients receiving dupilumab + TCS weekly or every 2 weeks vs placebo + TCS (64% and 69% vs 23%, respectively; P<.0001). Common AEs included injection site reactions and conjunctivitis.

- LIBERTY AD CAFÉ20: Phase 3 trial (n=325 randomized) assessing the efficacy and safety of dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every two weeks + medium potency TCS in adults with AD not controlled with/contraindicated use of cyclosporin A (CSA). Significantly more patients receiving dupilumab weekly and every two weeks) + TCS achieved EASI-75 (59.1% and 62.6%, respectively) vs placebo (29.6%, P<.001). Significant improvements in pruritus, pain, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression were also noted. AE rates overall were similar between study groups, with noted higher incidents of conjunctivitis with dupilumab and skin infections with placebo.

- LIBERTY AD OLE21: Phase 3 open-label extension study (n=2677 enrolled/treated, n=347 at week 148) assessing the efficacy and safety of dupilumab 300 mg weekly up to 148 weeks in adults with moderate-to-severe AD. Sustained improvements in the signs and symptoms of AD were noted (mean EASI: baseline parent study = 33.4; week 16 of OLE study = 5.8; week 148 OLE study = 1.5). Safety data was consistent with previous trials.

- LIBERTY AD HAFT22: Phase 3 trial (n=133 [adults: 106, adolescents: 27]) of adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic hand and/or foot dermatitis assessing efficacy of dupilumab monotherapy (adult dosing: 600 mg loading dose, then 300 mg every 2 weeks). At week 16, significant improvements from baseline vs placebo were observed in Hand/Foot (HF)-IGA 0 or 1 (40.3% vs 16.7%, P=.003), HF-Peak Pruritus NRS (52.2% vs 13.6%, P<.0001) and percent change in HF-modified total lesion score (-69.4% vs -31.0%, P<.0001). Those receiving dupilumab required rescue medication (typically TCS) less often than placebo (3% vs 21.2%). Common AEs included conjunctivitis and herpes infections; therapy discontinuations due to treatment-emergent AEs were 1.5% with dupilumab and 4.5% with placebo.

Lebrikizumab

- ADvocate 1 and 216: Two phase 3 trials (n=424 and 427, respectively) assessing efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab 250mg monotherapy in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD over 52 weeks. Compared to placebo, more patients receiving lebrikizumab at week 16 achieved an IGA score of 0 or 1 (ADvocate 1: 43.1% vs 12.7%, P<.001; ADvocate 2: 33.2% vs 10.8%, P<.001) and EASI 75 (ADvocate 1: 58.8% vs 16.2%, P<.001; ADvocate 2: 52.1% vs 18.1%, P<.001). Common AEs included conjunctivitis, AD exacerbation and skin infection, although the latter AEs (excluding conjunctivitis) were at lower incidence rates than placebo. The majority of AEs during the induction period were mild or moderate in severity, and did not lead to trial discontinuation.

Djoin28,29: Phase 3 trial (n=1153) in adults and adolescents aged 12 – 17 years evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of lebrikizumab. Three-year depth of response data showed that 50% of patients who responded to treatment at Week 16 and received once-monthly maintenance dosing achieved complete skin clearance (EASI 100 or IGA 0) at three years and that 87% achieved or maintained almost-clear skin (EASI 90) at three years. Additionally, over 83% of Week 16 responders taking lebrikizumab did not require concomitant TCS or TCI for the duration of the study.

Tralokinumab

- ECZTRA 1 and 224: Two phase 3 trials (n=802 and 794, respectively) assessing efficacy and safety of tralokinumab 300mg monotherapy in adults with moderate-to-severe AD with inadequate response to topical treatments. Compared to placebo, more patients receiving tralokinumab at week 16 achieved an IGA score of 0 or 1 (ECZTRA 1: 15.8% vs 7.1%, P=.002; ECZTRA 2: 22.2% vs 10.9%, P<.001) and EASI 75 (ECZTRA 1: 25.0% vs 12.7%, P<.001; ECZTRA 2: 33.2% vs 11.4%, P<.001). The majority of AEs were nonserious and mild or moderate in severity, with most resolved or resolving by the end of the treatment period; few patients had AEs leading to permanent discontinuation.

- ECZTRA 725: Phase 3 trial (n=277) of adults assessing efficacy and safety of tralokinumab 300mg + TCS in severe AD not controlled with/contraindicated use of cyclosporin A (CSA). Those receiving tralokinumab + TCS had higher EASI 75 responses at week 16 over placebo + TCS (64.2% vs 50.5%, P=.018). From week 16 to 26, more patients achieved EASI ≤7 (66.3% vs 44.7%). Similarly, those who previously failed CSA therapy also had higher responses with tralokinumab + TCS over placebo + TCS (57% vs 41%). Viral upper respiratory infections and headache were common AEs, as well as noted higher incidence of conjunctivitis over placebo (9.4% vs 4.4%).

- ECZTEND26: Phase 3 (ongoing) open-label extension study (safety analysis set n=1174; efficacy n=345) assessing the efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adults with moderate-to-severe AD over 5 years. At 2 years, 82.5% had sustained EASI 75 scores and 48.1% had sustained IGA 0 to 1 scores. The majority of AEs were mild to moderate and resolved, although 4.7% of participants experienced ≥ severe AE.

- ADHAND27: Phase 3 trial (n=402) evaluating tralokinumab monotherapy in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic hand eczema (ongoing). NCT05958407.

Trials in adolescents (ages 12-17 years)

Nemolizumab-ilto

- ARCADIA 1 and ARCADIA 2:21,22 These were two identically designed randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter Phase 3 trials. A total of 1278 subjects (includes 180 subjects aged 12 to 17 years) with moderate to severe AD were enrolled and treated for at least 1 year. Treatment groups consisted of nemolizumab in combination with TCS with or without TCI, or placebo in combination with TCS with or without TCI. Statistically significant improvement in both co-primary endpoints was seen after 16 weeks of treatment in the nemolizumab-treated subjects as compared to the placebo-treated subjects. Clear skin was achieved by 36% and 38% (ARCADIA 1 and ARCADIA 2, respectively) of nemolizumab-treated subjects when compared to the placebo group (25% and 26%, respectively; p<0.001). At least a 75% improvement in the eczema area and severity index score was achieved by 44% and 42% (ARCADIA 1 and ARCADIA 2, respectively) of nemolizumab-treated subjects as compared to the placebo group (29% and 30%, respectively; p<0.001). Both trials also met all key secondary endpoints which confirmed quick responses on itch (observed as early as one week after nemolizumab treatment initiation) and improvement in sleep disturbance. The safety profile was consistent between both the treatment and placebo groups with most treatment-emergent adverse events being mild to moderate in severity and non-serious. The most commonly occurring adverse events were headache at 5% and arthralgia, urticaria, and myalgia at 1%.

Dupilumab

- Dupilumab monotherapy in adolescents11: Phase 3 study (n=251) of adolescents aged 12-17 years with moderate-to-severe AD assessing efficacy and safety of dupilumab 200mg or 300mg every (Q) two weeks and dupilumab 300mg Q4 weeks vs placebo in those inadequately controlled by topical medications/topical therapy inadvised. At 16 weeks, significant improvements in EASI 75 from baseline were observed, with Q2 week regimen being superior to Q4 weeks (Q2 week: 41.5%, Q4 week: 38.1%, placebo 8.2%; P<.001). Common AEs of conjunctivitis, injection site reactions and lower non-herpetic skin infections were noted.

- LIBERTY AD PED-OLE28: Phase 3 open-label extension study (n=294) assessing the efficacy and safety of dupilumab 300mg every 4 weeks (irrespective of weight) up to 52 weeks in adolescents aged 12-17 years with moderate-to-severe AD who had participated in dupilumab parent trials. Most patients (70.9%) required an up titration to every 2 weeks dosing. By Week 52, almost half achieved IGA 0 to 1 (42.7%) and the majority had achieved EASI 75 (81.2%). Additionally, those with sustained IGA 0 to 1 for 12 weeks at week 52 (29.4%) stopped medication; 56.7% relapsed and were subsequently reinitiated on treatment, with a mean time to reinitiation of 17.5 (±standard deviation 17.3) weeks.

- LIBERTY AD HAFT20: Phase 3 trial (n=133 [adults: 106, adolescents: 27]) of adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic hand and/or foot dermatitis assessing efficacy of dupilumab monotherapy (adolescents ≥60 kg: 600mg loading dose, then 300mg every 2 weeks; adolescents <60kg: 400mg loading dose, then 200mg every two weeks). At week 16, significant improvements from baseline vs placebo were observed in Hand/Foot (HF)-IGA 0 or 1 (40.3% vs 16.7%, P=.003), HF-Peak Pruritus NRS (52.2% vs13.6%, P<.0001) and percent change in HF-modified total lesion score (-69.4% vs -31.0%, P<.0001). Those receiving dupilumab required rescue medication (typically TCS) less often than placebo (3% vs 21.2%). Common AEs included conjunctivitis and herpes infections; therapy discontinuations due to treatment-emergent AEs were 1.5% with dupilumab and 4.5% with placebo.

Lebrikizumab

- ADvocate 1 and 216: Two phase 3 trials (n=424 and 427, respectively) assessing efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab 250mg monotherapy in adults and adolescents (weight ≥ 40kg) with moderate-to-severe AD over 52 weeks. Compared to placebo, more patients receiving lebrikizumab at week 16 achieved an IGA score of 0 or 1 (ADvocate 1: 43.1% vs 12.7%, P<.001; ADvocate 2: 33.2% vs 10.8%, P<.001) and EASI 75 (ADvocate 1: 58.8% vs 16.2%, P<.001; ADvocate 2: 52.1% vs 18.1%, P<.001). Common AEs included conjunctivitis, AD exacerbation and skin infection, although the latter AEs (excluding conjunctivitis) were at lower incidence rates than placebo. The majority of AEs during the induction period were mild or moderate in severity, and did not lead to trial discontinuation.

- ADjoin:23,24 Phase 3 trial (n=1153) in adults and adolescents aged 12 – 17 years evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of lebrikizumab. Three-year depth of response data showed that 50% of patients who responded to treatment at Week 16 and received once-monthly maintenance dosing achieved complete skin clearance (EASI 100 or IGA 0) at three years and that 87% achieved or maintained almost-clear skin (EASI 90) at three years. Additionally, over 83% of Week 16 responders taking lebrikizumab did not require concomitant TCS or TCI for the duration of the study.

Tralokinumab

- ECZTRA 629: Phase 3 trial (n=289) of adolescents aged 12-17 years with moderate-to-severe AD assessing efficacy and safety of tralokinumab monotherapy with 150 mg and 300 mg dosing every two weeks. More patients receiving tralokinumab achieved IGA score of 0 or 1 (21.4% [P<.001] and 17.5% [P=.002]) and EASI 75 (28.6% [P<.001] and 27.8% [P<.001]) without rescue medication at week 16 over placebo (4.3% and 6.4% respectively). Efficacy was maintained in more than 50% of patients at week 52 (IGA 0 or 1: 33.3%, EASI 75: 57.8%). No new safety signals were identified and frequency of conjunctivitis was low (4.1% and 3.1% by dosing arms).

Trials in children (ages < 12 years)

Dupilumab

- LIBERTY AD PEDS30: Phase 3 trial (n=304) of children aged 6-11 years assessing efficacy of dupilumab (300 mg every 4 weeks or 200 mg every 2 weeks) + TCS vs placebo + TCS in those with severe AD. At week 16, significant improvements in AD signs, symptoms and QoL were observed in the dupilumab + TCS group (95% vs 61%, P<.0001), with improvements as early as week 2 and observed through week 16. Those achieving EASI 50 were similar across both dupilumab arms (95.1% and 92.7% respectively) vs placebo (61.0%, P<.0001).

- LIBERTY AD PED-OLE (ages 6-11)31: Phase 3 open-label extension study (n=254) assessing the safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of dupilumab (dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks) in children aged 6-11 years with severe AD up to 52 weeks. Uptitration to 200 or 300 mg every 2 weeks was permissible. By week 52, those achieving IGA 0 or 1 score was 41%, with 82% achieving EASI 75. Additionally, those with sustained IGA 0 to 1 for 12 weeks at week 52 (29%) stopped medication; 40% relapsed and were subsequently reinitiated on treatment, with a mean time to reinitiation of 13.5 (±standard deviation 5.2) weeks, suggesting continuation of treatment may be necessary for maintenance of clinical benefit. Common AEs included AD exacerbation, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infection, and conjunctivitis.

- LIBERTY AD PRE-SCHOOL32: Phase 2/3 trial (n=162) in children aged 6 months to 6 years assessing efficacy and safety of dupilumab + low-potency TCS in those with moderate-to-severe AD. At week 16, significantly more patients in the dupilumab group achieved IGA 0 or 1 (28%, P<.0001) and EASI 75 (53%, P<.0001) over placebo (4% and 11% respectively). AE of conjunctivitis had higher incidence in the dupilumab group (5% vs 0%); no AEs were serious or led to treatment discontinuation.

- LIBERTY AD PRE-SCHOOL-OLE33: Phase 3 open-label extension study (n=180) in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD assessing the safety of dupilumab (200 mg every 4 weeks (5-15kg) and 300 mg every 4 weeks (15-30kg)/200 mg every 2weeks (30-<60kg) up to 156 weeks. Dupilumab was generally well tolerated, with common AEs including AD exacerbation, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infection, and rhinorrhea. Most treatment-emergent AEs were mild-moderate, with 1.2% resulting in treatment discontinuation.

Tralokinumab

- TRAPEDS 134: Phase 2 trial (n=24) evaluating tralokinumab monotherapy in children ages 6-11 years (ongoing). NCT05388760.

- TRAPEDS 235: Phase 3 trial (n=195) evaluating tralokinumab +TCS in children and infants ages 6 months to <2 years and 2-11 years (ongoing). NCT06311682.

Diagnosis

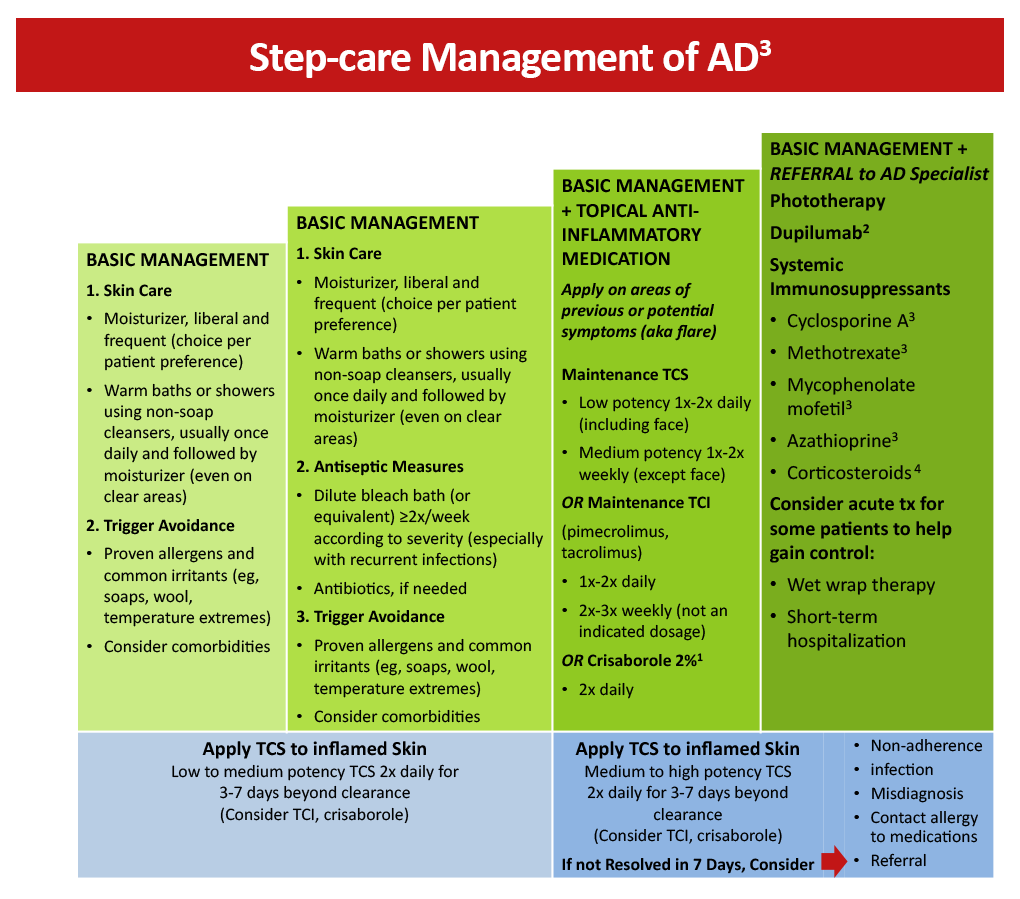

Due to a dysfunctional epidermal barrier, xerosis is common in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD). The application of moisturizers, especially after daily bathing, improves skin hydration, reduces disease severity, and decreases the need for pharmacologic agents. Moisturizers are the primary therapy for AD as they have been shown to minimize erythema, fissuring, and pruritus.1,2,3 If the patient does not respond to moisturizers and good skin care, topical medications are often added to therapy.

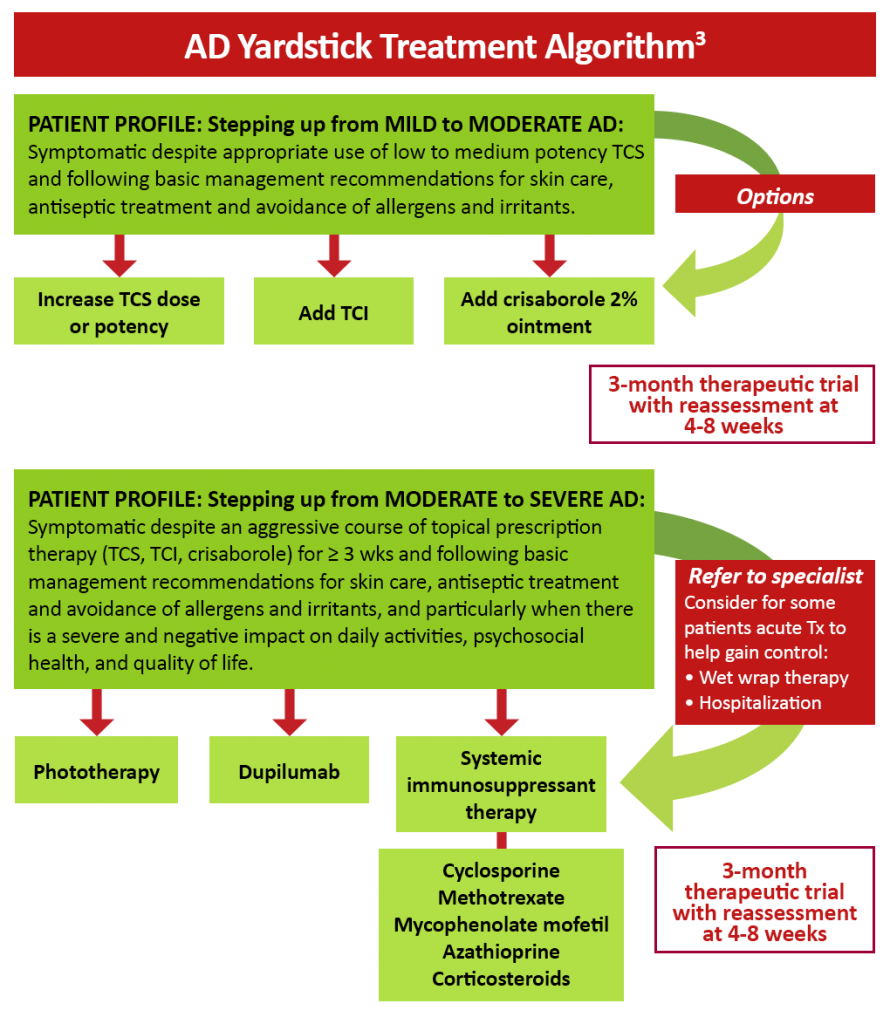

In mild to moderate AD, topical agents are effective in reducing inflammation, preventing flares, and alleviating pruritus and other symptoms of AD.4 Topical medications may be used in combination as they have different mechanisms of action and address different aspects of the pathogenesis of AD. Topical agents are also often used in conjunction with systemic or phototherapy in patients with severe AD.1 Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of topical corticosteroids (TCS), topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), or both. Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are the mainstay of anti-inflammatory therapy in adults and children with AD. TCS suppress immune responses and inhibit the release of proinflammatory cytokines. TCS minimize acute and chronic signs and symptoms of AD, including pruritus, and are used for active inflammatory disease and the prevention of relapse. It is suggested that once- to twice-daily application of TCS in commonly flaring areas may prevent relapses. The choice and strength of TCS are not established based on clinical evidence and usually depend on clinical judgment. Additional concerns with TCS use include a lack of a universal standard for quantity of application, higher absorption in children due to a proportionally greater body surface area to weight ratio, and the risk of systemic absorption in areas with thin skin.1,2

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) are a class of anti-inflammatory drugs that inhibit calcineurin-dependent T-cell activation, thereby blocking the production of proinflammatory cytokines and mediators responsible for the AD inflammatory reaction. There are 2 available TCIs: tacrolimus for moderate to severe disease and pimecrolimus for mild to moderate AD. TCIs are approved as second-line therapy for short-term, noncontinuous chronic treatment of AD in nonimmunocompromised individuals who failed to respond to other topical AD medications.1,2 Unlike TCS, TCIs do not cause cutaneous atrophy or affect collagen synthesis or skin thickness. TCIs may be used as steroid-sparing agents or in areas with thin skin. The most common side effects with TCI use are local stinging and burning upon application. These side effects tend to lessen after several applications or when preceded by a short period of TCS use. Patients should be warned of this side effect to prevent premature discontinuation. TCIs should not be used on infected lesions. Boxed warnings should be discussed before patient use, such as the controversial risk of malignancy (lymphoma and skin cancer) reported in patients using TCIs.1,2

Figure 1: Step-care management of AD3

Crisaborole 2% topical ointment is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved to treat mild to moderate AD in patients aged 3 months and older. Inhibition of PDE4 has been shown to decrease the production of cytokines and significantly alleviate pruritus. Based on safety and efficacy profiles, it is suggested that TCS be used for the treatment of symptom exacerbations, followed by long-term maintenance therapy with a lower dose of TCS and/or a TCI or crisaborole. Crisaborole may be used as a first-line agent in patients who cannot use TCS or TCI based on their established adverse event profile.3

Because of the chronic nature of AD, it is important that treatment options for long-term management of the disease are safe for prolonged use. Although topical treatment options are effective in minimizing the symptoms of AD, they may be associated with application site reactions and safety concerns with use over extended periods. Emollients and topical anti-inflammatory agents are often insufficient for individuals with moderate-to-severe disease.1,5 Systemic immunosuppressants may be prescribed but are off-label in many countries and are associated with considerable adverse effects that limit treatment duration.5,6

Figure 2: AD yardstick treatment algorithm3

The human monoclonal antibody dupilumab has been found to be effective in reducing the severity of moderate to severe AD in both adult and pediatric patients by targeting Th2 cell-mediated atopic immune responses.7,8,9 Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the IL-4 receptor α subunit that is able to block the signaling of the key Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13.10 Dupilumab is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of patients aged 6 months and older with moderate to severe AD whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical therapies. Additionally, dupilumab is approved for use in other atopic conditions, including moderate to severe asthma with eosinophilic phenotype and oral corticosteroid-dependent asthma in patients aged 6 years and older, and as add-on maintenance therapy for adults with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis.11

A brief summary of important clinical trials with dupilumab can be found below:

- In the SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 trials, the efficacy and safety of dupilumab was assessed in 671 adults with moderate to severe AD whose disease was inadequately controlled by topical treatment. In SOLO 1, a significant proportion of patients achieved a score of 0 or 1 on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) with dupilumab weekly and every other week compared to placebo (38% and 37% vs 10%; P < .001 for both regimens). Similar results were obtained in the SOLO 2 trial (36% and 36% vs 8%; P < .001 for both regimens). Dupilumab use was also associated with an improvement in quality of life (QoL) and a reduction in pruritus and symptoms of anxiety or depression.7

- The LIBERTY AD CHRONOS study found that the addition of dupilumab to standard topical corticosteroid therapy for 1 year significantly improved the signs and symptoms of AD in adults with moderate to severe AD and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids (TCS). At Week 16, a significantly greater number of patients in the dupilumab + TCS groups achieved IGA 0 or 1 compared to placebo + TCS (39% for both dupilumab groups vs 12%; P < .0001). EASI-75 was also achieved in a significantly greater number of patients receiving dupilumab + TCS weekly or every 2 weeks vs placebo + TCS (64% and 69% vs 23%, respectively; P < .0001).12

- The LIBERTY AD CAFÉ trial investigated the efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in adults with AD who were inadequately controlled with cyclosporine A (CsA) or who were intolerant to or unable to take CsA. A significant improvement from baseline in EASI-75 was observed with dupilumab weekly (59.1%) and every 2 weeks (62.6%) compared to placebo (29.6%) (both regimens, P < .001). Dupilumab use was also significantly associated with improvement in QoL and AD symptoms, including pruritus, pain, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression.13

- Dupilumab significantly improved AD signs, symptoms, and QoL in 251 adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe AD who were inadequately controlled with topical medications or for whom topical therapy was not advised. A significantly higher proportion of patients reached Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI-75) at Week 16 in the dupilumab every 2 weeks (41.5%) and every 4 weeks (38.1%) groups compared to placebo (8.2%) (both regimens, P < .001).8

- In children aged 6 to 11 years with severe AD inadequately controlled with topical therapies, every 4 weeks (Q4W) and every 2 weeks (Q2W) dupilumab plus TCS regimens resulted in statistically significant improvements in the signs, symptoms, and QoL of AD versus placebo plus TCS. A score of 0/1 on the IGA was achieved by 32.8%/29.5%/11.4% of patients in the Q4W/Q2W/placebo groups, respectively.9

- A phase 2 LIBERTY AD PRE-SCHOOL trial in children between 6 months and 6 years with severe AD found that dupilumab was generally well-tolerated and substantially reduced clinical signs and symptoms of AD. At Week 3, treatment with 3 and 6 mg/kg dupilumab reduced mean EASI scores by -44.6% and -49.7%, respectively, in children >2 years to <6 years, and by -42.7% and -38.8% in children >6 months to <2 years.14

- In the LIBERTY AD PED-OLE, open label extension study patients were enrolled under the original study protocol. Following protocol amendment, patients were switched to subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W) irrespective of weight, and newly enrolled patients were started on dupilumab 300 mg Q4W. By Week 52, 29.4% of patients had clear/almost clear skin sustained for 12 weeks and had stopped medication; 56.7% relapsed and were subsequently reinitiated on treatment, with a mean time to reinitiation of 17.5 (±standard deviation 17.3) weeks.15

- Tralokinumab, a monoclonal antibody and IL-13 antagonist, is also FDA-indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable.16

- Results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and 2) found treatment to be superior to placebo.17 At week 16 of the trials more patients in the tralokinumab arms achieved an IGA score of 0 or 1 (15.8% vs 7.1%-ECZTRA 1 and 22.2% vs 10.9%-ECZTRA 2) and EASI 75 (25.0% vs 12.7%-ECZTRA 1 and 33.2% vs 11.4%-ECZTRA 2).17 The majority of adverse events (AEs) were nonserious and mild or moderate in severity, with most resolved or resolving by the end of the treatment period; few patients had AEs leading to permanent discontinuation.17

References

- Sidbury R, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:e1-e20.

- Quality of Life. Taber’s Medical Dictionary Online 24th Edition, Taber’s online. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.tabers.com/tabersonline/view/Tabers-Dictionary/750945/all/quality_of_life?q=Life+Quality+of

- Kaufman B, Alexis A. Eczema in Skin of Color: What You Need to Know. National Eczema Association. Updated September 22, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2025. https://nationaleczema.org/blog/eczema-in-skin-of-color/

- Prescription Injectables for Eczema. National Eczema Association. Medically reviewed April 21, 2025. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://nationaleczema.org/treatments/injectables/#:%7E:text=Inject…ologics%20and%20steroids

- Dupixent. Prescribing information. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC.; 2025. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/dupixent_fpi.pdf

- Ebglyss. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2025. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://uspl.lilly.com/ebglyss/ebglyss.html#pi

- Adbry. Prescribing information. LEO Pharma Inc.; 2024. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://mc-df05ef79-e68e-4c65-8ea2-953494-cdn-endpoint.azureedge.net/-/media/corporatecommunications/us/therapeutic-expertise/our-product/adbrypi.pdf?rev=d8ced7cbd6874a6997427ab88a2093e0#page=19

- Nemluvio. Prescribing information. Galderma Laboratories, L.P.; 2024. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://www.galderma.com/sites/default/files/2024-12 Nemluvio_Dual%20PI%20for%20website%2013Dec24.pdf

- Vtama. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Co.; 2024. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://vtama.com/PI/

- Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Hevert AA, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily: significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults and children down to 2 years of age in the pivotal phase 3 ADORING trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91(3):457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.05.023. Primary results from two Galderma phase III clinical trials in atopic dermatitis published in The Lancet. Press release. Published July 25, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://www.galderma.com/news/phase-iii-arcadia-1-and-2-trial-primary-results-published-lancet-galdermas-nemolizumab#

- Boguniewicz M, et al. Expert perspectives on management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A multidisciplinary consensus addressing current and emerging therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1519-1531.

- Davis DMR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with phototherapy and systemic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:e43-e56.

- Hamilton JD, Ungar B, Guttman-Yassky E. Drug evaluation review: Dupilumab in atopic dermatitis. Immunotherapy. 2015;7:1043-1058.

- Simpson EL, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348.

- Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56.

- Paller AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1282-1293.

- Dupixent. Prescribing information. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC.; 2025. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/dupixent_fpi.pdf

- Adbry. Prescribing information. LEO Pharma Inc.; 2024. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://mc-df05ef79-e68e-4c65-8ea2-953494-cdn-endpoint.azureedge.net/-/media/corporatecommunications/us/therapeutic-expertise/our-product/adbrypi.pdf

- Ebglyss. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2025. Accessed June 23, 2025. https://uspl.lilly.com/ebglyss/ebglyss.html#pi

- Silverberg JI, et al. Two phase 3 trials of lebrikizumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1080-1091.

- Primary results from two Galderma phase III clinical trials in atopic dermatitis published in The Lancet. Press release. Published July 25, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://www.galderma.com/news/phase-iii-arcadia-1-and-2-trial-primary-results-published-lancet-galdermas-nemolizumab

- Nemluvio. Prescribing Information. Galderma Laboratories, L.P.; 2024. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://www.galderma.com/sites/default/files/2024-12/Nemluvio_Dual%20PI%20for%20website%2013Dec24.pdf

- Sidbury R, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Worm M, et al. Efficacy and safety of multiple dupilumab dose regimens after initial successful treatment in patients with atopic dermatitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:131-143.

- Blauvelt A, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): A 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: A placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:1083-1101.

- Beck LA, et al. Dupilumab provides favorable safety and sustained efficacy for up to 3 years in an open-label study of adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:567-577.

- Long-term Safety and Efficacy Study of Lebrikizumab (LY3650150) in Participants With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis (ADjoin). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04392154. Updated June 15, 2025. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04392154?id=NCT04392154&rank=1&tab=table

- Lilly’s EBGLYSS® (lebrikizumab-Ibkz) single monthly maintenance injection achieved completely clear skin at three years in half of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Press release. Published March 07, 2025. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lillys-ebglyssr-lebrikizumab-lbkz-single-monthly-maintenance

- Simpson EL, et al. Dupilumab treatment improves signs, symptoms, quality of life, and work productivity in patients with atopic hand and foot dermatitis: Results from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024:90:1190-1199.

- Wollenberg A, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:437-449.

- Gutermuth J, et al. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids in adults with severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to or intolerance of ciclosporin A: A placebo-controlled, randomized, phase III clinical trial (ECZTRA 7). Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:440-452.

- Blauvelt A, et al. Long-term 2-year safety and efficacy of tralokinumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Interim analysis of the ECZTEND open-label extension trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;4:815-824.

- A 32-week Trial to Evaluate the efficacy and Safety of Tralokinumab in Subjects With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Hand Eczema Who Are Candidates for Systemic Therapy (ADHAND). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05958407. Updated February 24, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05958407?id=NCT05958407&rank=1

- Blauvelt A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results through week 52 from a phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365-383.

- Paller AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: The phase 3 ECZTRA 6 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:596-605.

- Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab provides clinically meaningful responses in children aged 6-11 years with severe atopic dermatitis: Post hoc analysis results from a phase III trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:787-798.

- Cork MJ, et al. Dupilumab safety and efficacy in a phase III open-label extension trial in children 6-11 years of age with severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:2697-2719.

- Paller AS, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. 2022;400:908-919. Reference 40 – replace only the strikethrough with the following: Poster presented at: 81st Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, March 2023; New Orleans, LA. https://aad-eposters.s3.amazonaws.com/AM2023/poster/42924/Treatment-Emergent

- Paller AS, et al. Treatment-emergent adverse events in patients aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab in an open-label extension clinical trial.

- Tralokinumab Monotherapy for Children With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis – TRAPEDS 1 (TRALokinumab PEDiatric Trial no. 1). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05388760. Updated July 24, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05388760

- A Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Tralokinumab in Combination With Topical Corticosteroids in Children and infants with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis (TRAPEDS 2). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06311682. Updated July 17, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06311682

References

- Eichenfield LF, Ahluwalia J, Waldman A, Borok J, Udkoff J, Boguniewicz M. Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: A comparison of the Joint Task Force Practice Parameter and American Academy of Dermatology guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4 suppl):S49-S57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.009

- Schneider L, Tilles S, Lio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis: A practice parameter update 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:295-299.e27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.672

- Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman-Yassky E, Ong PY, Silverberg J, Farrar JR. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: Practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120:10-22.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2017.10.039

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.046

- Boguniewicz M, Alexis AF, Beck LA, et al. Expert perspectives on management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A multidisciplinary consensus addressing current and emerging therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1519-1531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.005

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1610020

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1282-1293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054

- Hamilton JD, Ungar B, Guttman-Yassky E. Drug evaluation review: Dupilumab in atopic dermatitis. Immunotherapy. 2015;7:1043-1058. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt.15.69

- Dupixent® (dupilumab) prescribing information. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2023. https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/dupixent_fpi.pdf

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): A 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1

- de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: A placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:1083-1101. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16156

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Simpson EL, et al. A phase 2, open-label study of single-dose dupilumab in children aged 6 months to <6 years with severe uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: Pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:464-475. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16928

- Blauvelt A, Gutman-Yassky E, Paller A, et al. Long‑term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate‑to‑severe atopic dermatitis: Results through week 52 from a phase III open‑label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED‑OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365-383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2

- Tralokinumab (Adbry®️) Prescribing information (PI) 2023 (https://mc-df05ef79-e68e-4c65-8ea2-953494-cdn-endpoint.azureedge.net/-/media/corporatecommunications/us/therapeutic-expertise/our-product/adbrypi.pdf?rev=64ed2d0493af4881bede5853dde9f5bf). Accessed 12/1/23.

- Wollenberg A, Blauvelt D, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:437-449.